Biodiversity is a Good Thing, in music as in biology. Throughout the sixteenth century the lute lived in peaceful co-existence with numerous other plucked species, now largely forgotten. Let's meet some of them.

When Francesco da Milano published his first book of tablature in 1536 he described the music as being for "viola o vero lauto". Which does not mean "viola or true lute" but simply "viola or lute". This isn't a viola in the modern sense, but the viola da mano ("hand"), an instrument similar to to the lute but shaped more like a guitar. The name distinguishes it from the viola da gamba ("leg"), which was held between the legs and played with a bow. The viola da mano makes frequent appearances in Baldassare Castiglione's classic manual of life at court in Italy, Il Cortegiano (15xx) . Thomas Hobie's English version of the book (15xx) translates viola da mano as "lute", evidence that the viola remained localised.

But it did hop over the water to Spain, where it was known as the vihuela de mano. Maybe not surprising, since much of eastern Spain was under Italian control at the time. [check details] There was no lute music published in Spain in the sixteenth century, but seven substantial books for vihuela exist, with evocative titles:

[table of titles]

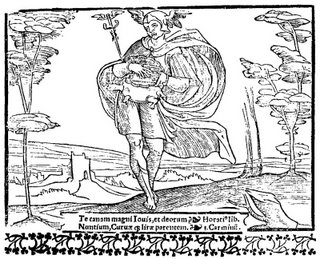

Narvaez (or Narbaez, as he spelt it) really did name his Seys libros del Delphin after a dolphin. The frontispiece shows a splendid sea-creature, ridden by the mythological Greek [musician] Arion.

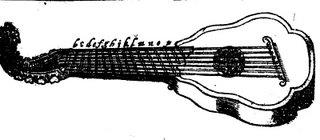

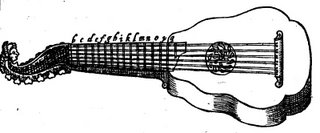

William Barley's A new Booke of Tabliture (1596), the first of its kind to be published in England, presented music for the lute, orpharion and bandora. Helpfully, he provides pictures and descriptions of each instrument.

The orpharion was tuned like a lute but had wire strings and a strangely diagonal bridge and frets. Presumably its name derives from Orpheus. It's not clear why Barley assigned some pieces to lute and others to orpharion since there's no clear stylistic difference between the two sets. When John Dowland published his first three books of songs shortly afterwards, he specified that the accompaniments could be played on lute or orpharion. It didn't last much longer.

The orpharion was tuned like a lute but had wire strings and a strangely diagonal bridge and frets. Presumably its name derives from Orpheus. It's not clear why Barley assigned some pieces to lute and others to orpharion since there's no clear stylistic difference between the two sets. When John Dowland published his first three books of songs shortly afterwards, he specified that the accompaniments could be played on lute or orpharion. It didn't last much longer. The bandora (or pandora) is another wire-strung beast, bigger than the lute and with an idiosyncratic tuning. It's probably best known as one of the band in Thomas Morley's consort lessons (1599), written for the hard-to-find combination of flute, treble viol, bass viol, lute, bandora and cittern. Here they are, happily thrumming away at a feast for Sir Henry Unton, Queen Elizabeth's ambassador to France, in 1596.

The bandora (or pandora) is another wire-strung beast, bigger than the lute and with an idiosyncratic tuning. It's probably best known as one of the band in Thomas Morley's consort lessons (1599), written for the hard-to-find combination of flute, treble viol, bass viol, lute, bandora and cittern. Here they are, happily thrumming away at a feast for Sir Henry Unton, Queen Elizabeth's ambassador to France, in 1596.

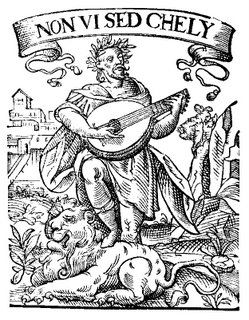

The cittern enjoyed a surprisingly long and varied life (surprising, that is, if you have heard one). Like a flat-backed mandolin with ukulele tendencies, the standard cittern was confusingly tuned b-g-d'-e' [show this in staff notation] and was to be found hanging on the walls in barbers' shops. Lutenists inexplicably flocked to write for it, including Sixtus Kärgel (Renovata Cythara, 1578), Anthony Holborne (The Cittharn School, 1597) and Thomas Robinson, whose New Citharen Lessons of 1609 includes pieces for a scarcely-imaginable monster 14-course cittern. The instrument evolved into the English Guitar, a wire-strung instrument tuned to a C major chord, for which the famed Italian violinist Francesco Geminiani wrote a method (1760), and in Germany into the exquisitely named Hamburger Citrinchen.

But these are mainstream compared with the penorcon or stump, varieties of bass cittern about which virtually nothing is known. Or the gittern, on no account to be confused with the cittern.

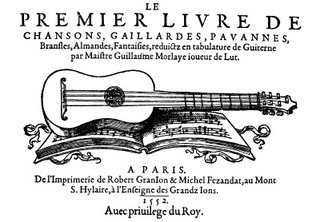

The ultimate predator, the guitar, occupied a modest place in the sixteenth century. It was an undernourished creature with four pairs of strings. Lutenists, most of them French for some reason, indulgently published music for the harmless little fellow: Pierre Attaignant, Guillaume Morlaye, Adrien le Roy, Albert de Rippe.

Little did they realise what they were nurturing, and how the guitar would knock the lute over the head in the following century, becoming the favourite instrument of the Sun King, Louis XIV, himself.

Little did they realise what they were nurturing, and how the guitar would knock the lute over the head in the following century, becoming the favourite instrument of the Sun King, Louis XIV, himself.