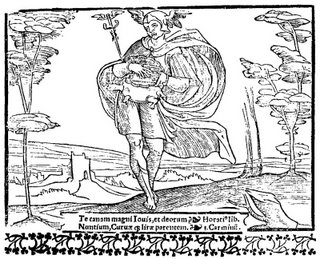

The frontispiece of Alonso de Mudarra's Tres Libros de Musica, published in Sevilla in 1546, shows the god Mercury, recognisable by his winged helmet, his caduceus (a winged staff with a pair of snakes) and his lyre. The lyre has legs and a head. It's a tortoise, and none too happy.

The frontispiece of Alonso de Mudarra's Tres Libros de Musica, published in Sevilla in 1546, shows the god Mercury, recognisable by his winged helmet, his caduceus (a winged staff with a pair of snakes) and his lyre. The lyre has legs and a head. It's a tortoise, and none too happy.The Latin quotation below the picture is from Horace's Ode 1:10, To Mercury.

Te canam magni Iovis, et deorum

Nuntium, Curvaeque lirae parentem

I sing to you, messenger of great Jove and of the gods, and father to the curved lyre

Precocious Mercury, on the day of his birth, scooped out the insides of a tortoise, stretched leather across the front, added gut strings and thus invented the lyre, which he later had to give to Apollo in exchange for the cattle which Mercury had stolen from him.

Which explains, after a fashion, how Testudo (meaning tortoise) came to be the Latin name for the lute in the sixteenth century. Emmanuel Adriaensen, Joachim van den Hove, Jean-Baptiste Besard and others described their music as being for the Testudo. Giovanni Pacolini published songs for a family of three different-sized tortoises in Tribus testudinibus ludenda Carmina (Louvain, 1564). After Georg Leopold Fuhrmann's splendidly titled Testudo Gallo-Germanica (Nürnberg, 1615) there was nowhere left to go and the tradition died out.

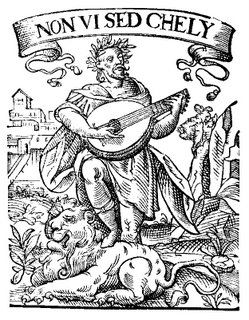

Other classically-minded composers used the equivalent Greek term Chelys (from chelone, 'tortoise'). The motto, Non vi sed chely, from the title page of Matthias Reymann's Noctes Musicae (Leipzig, 1598), echoes Willet's Emblemata (Cambridge, 1592).

Other classically-minded composers used the equivalent Greek term Chelys (from chelone, 'tortoise'). The motto, Non vi sed chely, from the title page of Matthias Reymann's Noctes Musicae (Leipzig, 1598), echoes Willet's Emblemata (Cambridge, 1592).Non vi sed virtute, non armis sed arte paritur victoria

Not by force but by virtue, not with arms but with art is victory won

In a neat extension of the animal symbolism, the picture shows Orpheus taming a wild beast with his music.

Postscript:

Turtels & twins, courts brood, a heauenly paier

This line from Dowland's famous lute song Fine Knacks for Ladies (1600) refers, misleadingly, not to the Testudo but to the turtle dove.